Many Christians have been taught that the doctrine of Jesus’ deity and the doctrine of the Trinity can be traced from the pages of Scripture to today’s Orthodoxy. If this is the case, early Christian writings that predate the Church councils and creeds should contain teachings or references to the doctrines. So, what do the authors of the Didache, the first century Church instruction manual, have to say about God? Who do they understand Jesus to be? Is the doctrine of the Trinity expressed within its pages? This post will examine the evidence to determine if the document supports today’s Orthodoxy.

What is the Didache?

Didache (pronounced did-ah-kay) is the Greek word for teaching. It is the shortened name of the first century document used by the early Church for the assimilation of Gentiles into the Christian faith. The guidebook also bears the title, “The Lord’s Teaching of the Twelve Apostles,” and “The Teaching of the Lord to the Gentiles by the Twelve Apostles.”

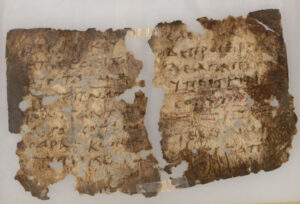

Penned, not by the twelve apostles, but by unknown authors between 50 to 100 C.E., excerpts from the Didache first appeared only through records of early Christian writers such as Clement of Alexandria (150 to c. 211 CE)[1], Origen (c. 185 to c. 253), and Athanasius (c. 296 to 373 CE) who referenced the material or quoted from it directly.[2] Eusebius of Caesarea (260 CE to 339 CE) also spoke of the work in his early 4th century Ecclesiastical History[3], and it appears in a 4th century collection of early Christian church law titled Apostolic Constitutions. However, it wasn’t until 1873 that a complete manuscript, dated to about 1056 C.E., was found by Philotheos Bryennios in the Jerusalem Monastery of the Most Holy Sepulcher in Constantinople.[4] He later published the reclaimed manuscript in 1883.

Why It Is Important

Depending on the translation, the Didache is only about 3,000 words. Yet, its brevity belies its importance as the earliest extant catechism on Christian morality and liturgical matters for non-Jewish believers.

Style variance and content lead scholars to believe the manuscript is a composite document. Divided into four sections, the first section appears to be a redaction of a Jewish document regarding the Two Ways, while the remaining sections are thought to be the work of early Christian writers.

The Didache predates most of the New Testament, but many scholars believe it and the gospel of Matthew share a source material since they contain similar teachings and phrases. Other similarities come from Old Testament books like Exodus and Deuteronomy, and New Testament writings such as Luke, Galatians, Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, and 1 Timothy.

Although the Didache is not a theological treatise per se, we can learn much about the authors’ theology and Christology from its pages.

Who is God in the Didache?

“God” is mentioned in this early Church manual twelve times[5], including once as the “God of David,” a distinctly Jewish title.[6] Unlike the Church creeds of the fourth century, which portray God as a tri-personal being, this work depicts God as a single person as evidenced by the use of a single person pronoun.[7] This view is in keeping with God’s revelation in the Shema, “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.”[8] More specifically, this singular God is called “Father” or “our Father” eight times, a designation that is often used by Jesus in the New Testament.

God is portrayed as being sovereign over creation, in that catechumens are reminded that “nothing apart from God comes to pass.”[9] Moreover, the new converts are taught that the kingdom belongs to the Father[10] who is the Almighty and who created all things for His name’s sake.[11] Prayer is offered to “our Father”[12] and it is His will that is to be followed.[13] God is the ultimate judge of prophets and parents are exhorted to instruct their children in the “fear of God.”[14] In addition, eight times we read that glory is to be given to God the Father, and three times power is ascribed to Him. Neither is given to Jesus or the Spirit.

Who is Jesus in the Didache?

The Didache’s first century authors taught Gentile catechumens that Jesus was the Christ, the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew Messiah. Christ, which means anointed, is used twice.

Four times, Jesus is designated as being the servant of God with the phrase “Your servant.”[15] This is in keeping with Old Testament prophecies that refer to the coming Messiah as the servant of God, most famously in the writings of the prophet Isaiah.

Jesus is never referred to as God, the God-Man, God the Servant, or any other reference to deity. If Jesus is God, it would seem imperative to instruct new Gentile converts that the God of the Jewish Fathers was not simply the One God, as had been taught for centuries, but He is actually a “They”—a tri-personal being that includes Jesus and a nameless Holy Spirit. But such divine designations are noticeably absent from this early Christian document.

Who is the Holy Spirit in the Didache?

Four times the Didache addresses a prophet who speaks in the Spirit and once, it speaks of someone being called and prepared by the Spirit.[16] The term “Holy Spirit” is used twice, both of which occur in what is referred to as a baptismal formula. (More about this in a moment.) The Holy Spirit is never said to be a separate person from God the Father and Jesus. The Spirit has no name, is not prayed to, given glory, or designated as God.

Who is the Lord in the Didache?

The title “Lord” (Greek κυριος) appears twenty-three times, not counting occurrences in the manual’s title. It is not a divine title per se, as it simply means “lord” or “master.” It is used of both humans and deity in the New Testament.

All but one occurrence of “Lord” is a reference to Jesus. The exception is found in chapter 10, where the context determines it is about God, who is the Father and not His servant.[17]

“Master” (Greek δεσποτα) occurs only twice. Like the title “Lord,” it is not specific to deity. The first occurrence is in chapter 4, where the reference is to a human lord. The second occurrence is used to denote the Almighty who created all things and is a reference to God and not Jesus.[18]

“Master” is translated by some as “Lord,” but “Master” is the better rendering as it helps English readers distinguish it from “Lord” (κυριος), which is used of Jesus, who is not the Almighty but the servant of the Almighty.

Is the Trinity in the Didache?

Before discussing the doctrine of the Trinity in the Didache, it is important to understand the basic teaching of the doctrine, which states that God is a tri-personal being: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. All three persons are considered co-equal, co-eternal (uncreated), and consubstantial (all the same substance or essence). Although there are three persons, there is only one God.

Is there evidence that the manual’s authors believed in a triune God? Just as the word “Trinity” does not appear in the Bible, it is absent from the Didache as well. Nevertheless, because catechumens are twice instructed to be baptized “in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”[19], many are quick to interpret this as proof of a first-century belief in a tri-personal God.

The baptismal formula, which also appears at the end of Matthew’s gospel[20], does not offer a statement or explanation as to the relationship between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. For example, nowhere in the Didache are we told that the Son and the Holy Spirit are God. Indeed, Jesus is only referred to as Christ, Lord, and the servant of God. Moreover, new converts are never told, nor is it implied that the three share a singular God-substance (consubstantial), making them not three persons but one God. Neither are they told, nor is it implied that the three are co-equal and co-eternal (uncreated). Historically and Scripturally speaking, this is not surprising since scholars acknowledge the doctrine of the Trinity was developed over time, and it was not codified until the fourth century. Thus, to presume that the authors’ inclusion of the words “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” is proof of a doctrine not explicitly taught in Scripture and one that would not be developed for another 300-400 years is misguided.

In addition, many scholars believe the Didache is a composite document, lending credence to the idea that the tri-person formula is a later addition to the manual. The inclusion of the instruction that converts can receive the Eucharist only if they have been “baptized in the name of the Lord”–without mention of the triadic formula–[21], is presented as internal evidence in support of this position[22].

Instead of a declaration of the existence of a multi-person God, the baptismal formula should be understood in light of the document’s theology and Christology. As we have seen, the Father alone is called God, while Jesus is the Christ, the servant of God. The Spirit, designated as holy, is the power by which the prophets speak.

In a letter that is contemporary with the Didache, Clement of Rome wrote in c. 96 CE to the church in Corinth:

1st Corinthians 46 – Or, do we not have one God and one Christ and one Spirit of grace, a Spirit that was poured out upon us?[23]

Like in the Didache’s Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the juxtapositioned words “God,” “Christ,” and “Spirit” do not teach nor imply a doctrine of a triune God but rather illustrate the very distinction between them. One is God. One is Christ. One is the Spirit that empowers believers.

The Significance of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”

What, then, is the significance of the baptismal formula? To perform a baptism in someone’s name is to acknowledge the authority in the new convert’s life. God delegated His authority to Jesus, and the new convert is made his disciple through baptism. What’s more, the baptized believer is now empowered by the Spirit to live a life of obedience to that authority.

It is important to note that the Bible never records anyone baptized using the triadic formula. Indeed, the book of Acts documents nine instances where individuals or groups of people are baptized. Of those nine, four provide us with specific details. In each situation, converts are baptized in the name of Jesus.[24] The Trinitarian baptismal formula is completely absent from New Testament practice, leading some Biblical scholars to surmise the formula is a later addition.[25]

Conclusion

Contrary to popular belief, the doctrine of the Trinity cannot be traced in an unbroken line from Scripture to today’s Orthodoxy. There is no evidence of a belief in a triune God in the Didache, the earliest extant Christian instructional manual. On the contrary, God is one person, as evidenced by the use of singular pronouns. He is the Father, the Almighty, sovereign over His creation. He is to be feared, petitioned in prayer, and glorified.

Jesus is not referred to or spoken of as being God. He is not depicted as sovereign, all powerful, or the Creator. Neither does the Didache instruct catechumens to pray to him or to fear him. Instead, Jesus is God’s servant through whom God the Father has made known “knowledge, faith, and immortality.”[26] The Spirit is the way God empowers believers.

[1] F. R. Montgomery Hitchcock, Did Clement of Alexandria Know the Didache? The Journal of Theological Studies, Volume os-XXIV, Issue 96, July 1923, Pages 397–401.

[2] Thomas V. Mirus, Church Fathers: The Didache and the Epistle of Barnabas, In Fathers of the Church, Aug 19, 2014,

[3] Eusebius, “Ecclesiastical History,” Book 3, chapter 25. The Greek historian refers to it as the “Teachings of the Apostles.”

[4] The manuscript was a part of the Codex Hierosolymitanus, a collection of texts by the Apostolic Fathers.

[5] Not included in the ten occurrences of “God” is the term “gods” in Chapter 6, which is used once to denote idols. Idols are said to be “dead gods.”

[6] The Biblical teachings and that of the first century Church are completely compatible with Jewish theology. See Dr. Joshua Schachterle, Jewish and Christian Traditions in the Didache, The Bible and Beyond, accessed 12/24.

[7] Didache 4.10. Used in reference to God, the verb “come” is used in the third person singular form. The Interlinear Didache, One Messianic Gentile, accessed 11-05-24.

[8] Deuteronomy 6:4-9, English Standard Version.

[11] Didache, Chapters 5 and 10 (creation is the handiwork of God).

[13] Didache, Chapters 1 and 8.

[15] “Your” in these occasions is a singular person in Greek.

[17] Some may contend that “Lord” in Chapter 16 refers to God since the author quotes Zechariah 14:5. In this Old Testament passage, the title “LORD” is used by English translators as a substitute for the name Yahweh. The authors apply the passage to Jesus since God has made him both Lord and Christ (Acts 2:36), and has given him authority over the Church (Ephesians 1:22-23).

[20] Matthew 28:18-20.

[22] Aaron Milavec, The Didache: Faith, Hope, and Life of the Earliest Christian Communities, 50-70 CE, Newman Press, NY 2003, p.271.

[23] The Catholic Library, First Epistle to the Corinthians.

[24] Acts 2:37-38 and 41; Acts 8:12, 14-17; Acts 10:46-48; Acts 19:1 and 3-5.

[25] Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: An Examination of Matthew 28:19.